what adaptations allows the bird to stay in flight?

Information technology is widely accustomed that the start bird, Archaeopteryx lithographica, evolved approximately 150 million years ago. Since and then, many adaptations have been sculpted by natural selection, making birds the unique group they are today. These adaptations help birds to survive and thrive in all environments, on every area of the planet. Three physical characteristics in item point unique adaptations to their environment: beaks (bills), feet, and plumage (feathers).

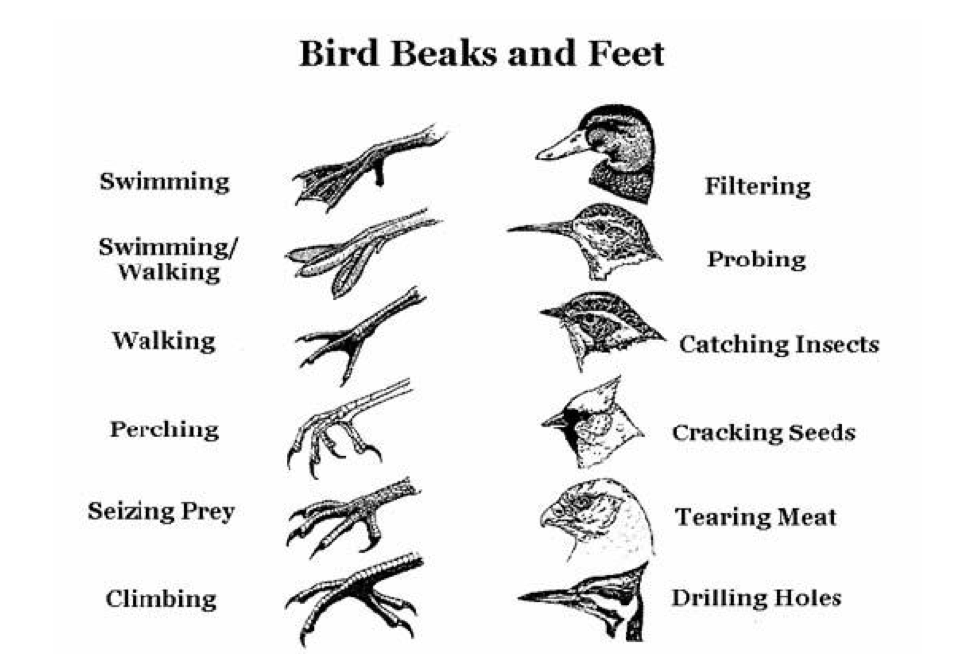

University of Houston Photo – The adaptive characteristics of nib and foot structure optimize a bird'due south ability to thrive in its surroundings

University of Houston Photo – The adaptive characteristics of nib and foot structure optimize a bird'due south ability to thrive in its surroundings

Natural selection is the mode of evolution that makes living things well-suited (adjusted) to their environments. This mechanism has sculpted the beaks, anxiety, and plumage of birds over millions of years, making these animals more successful in their environments. Varieties of beak shapes and sizes are an adaptation for the different types of foods that birds eat. In general, thick, strong conical beaks are great at breaking tough seeds, and are constitute on seed-eating birds such equally cardinals, finches, and sparrows. Hooked beaks, such equally those institute on raptors similar hawks, eagles, falcons, and owls, are proficient at fierce meat – perfect for these predatory birds. Direct beaks of intermediate length are particularly versatile and are often found on omnivorous birds like crows, ravens, jays, nutcrackers, and magpies. In that location are even highly specialized bills such every bit the flamingo's: their beaks are comma-shaped for filter-feeding, enabling them to sift through mud and silt in gild to devour krill and other crustaceans.

NPS Photograph/Patricia Simpson – The conical beak of a Firm Sparrow (Passer domesticus) is great at breaking seeds

NPS Photograph/Patricia Simpson – The conical beak of a Firm Sparrow (Passer domesticus) is great at breaking seeds

NPS Photo/Patrcia Simpson – The versatile bill of an omnivorous Mutual Raven (Corvus corax)

NPS Photo/Patrcia Simpson – The versatile bill of an omnivorous Mutual Raven (Corvus corax)

The anxiety of birds take evolved as an adaptation to the landscapes they inhabit. Wading birds, such as egrets and herons, accept long toes to help with weight distribution as they make their manner over reeds and lily pads. Ducks and pelicans have webbed feet which, much similar SCUBA fins, make them more practiced swimmers. Some birds, such as the American Coot, have lobate feet - a "halfway" point between webbed feet and long-toed waders to aid in both modes of locomotion. Many bird species, like well-nigh songbirds, are also referred to as "perching birds" because they accept a human foot structure that allows them to grasp branches - the configuration of one toe at the back of the foot acts similar a pincher, stabilizing the perched bird.

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – 3 toes in the front end and one toe in the back make perching like shooting fish in a barrel for this Blackness Phoebe (Sayornis nigricans)

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – 3 toes in the front end and one toe in the back make perching like shooting fish in a barrel for this Blackness Phoebe (Sayornis nigricans)

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – Webbing between the forepart toes (palmate) gives this Heermann'south Gull (Larus heermanni) a paddling advantage in the ocean

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – Webbing between the forepart toes (palmate) gives this Heermann'south Gull (Larus heermanni) a paddling advantage in the ocean

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – This California Dark-brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus) is ocean adapted with webbing between all 4 toes (totipalmate) and a giant bill with a large fish-storing pouch

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – This California Dark-brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus) is ocean adapted with webbing between all 4 toes (totipalmate) and a giant bill with a large fish-storing pouch

Smash structure plays an additional role in foot adaptation: the acute, potent nails of woodpeckers and flickers gives these species the power to stand on and climb the vertical trunks of trees, a useful adaptation for reaching insects that couch beneath the bark. The grasping, sharp claws of a raptor, on the other hand, are honed for subduing and even killing casualty. Most running birds, such as ostriches and emus, do not perch, therefore their back hook is either reduced or entirely absent.

Feather, or a bird'southward feather blueprint, is also shaped by natural option for two master reasons (likewise the obvious benefit of flight): mating and survival. Both of these categories increment individual fitness, which is the measurement of an organism'due south ability to survive and procreate. Plumage that is attractive to the reverse sex allows for more mating opportunities and, thus, the ability to create more young. Additionally, feathers can disguise an organism, creating camouflage for those that wish to hibernate from predators, or to sneak up on prey. Cryptically colored (camouflaged) birds tend to resemble the background they wish to hide against: the mottled blackness and brown plumage of nocturnal nightjars, for example, helps them to blend in against the woody ground or tree branches as they roost during daylight hours. The specialized flight feathers of owls, on the other mitt, are fringed for silent flying, making owls near impossible to detect equally they dive down upon prey.

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – The flashy pinkish of a male Anna'southward Hummingbird (Calypte anna) gorget helps them to garner the attention of females

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – The flashy pinkish of a male Anna'southward Hummingbird (Calypte anna) gorget helps them to garner the attention of females

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – A Greater Roadrunner's (Geococcyx californianus) plumage helps information technology to blend in to the leafage of its environment

NPS Photo/Patricia Simpson – A Greater Roadrunner's (Geococcyx californianus) plumage helps information technology to blend in to the leafage of its environment

Here at Cabrillo National Monument (CNM), there are many different types of birds. Located on the great Pacific Flyway, CNM houses both residential and migratory shorebirds, seabirds, raptors, and songbirds. From the California Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis californicus)

to the California Gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica), CNM is a great location to birdwatch. So come on down to view our feathered friends! And the adjacent time you notice a bird, whether it's at the Monument or elsewhere, take a wait at its beak, feet, and feathers to recognize its incredible adaptations!

References

All almost birds:

https://university.allaboutbirds.org/

For more data about beaks and foraging (eating):

http://projectbeak.org/adaptations/beaks_cracking.htm

https://www.thespruce.com/bird-foraging-behavior-386457

For more information about feet:

http://projectbeak.org/adaptations/anxiety.htm

http://fsc.fernbank.edu/Birding/bird_feet.htm

Source: https://www.nps.gov/cabr/blogs/the-remarkable-adaptations-of-birds-to-their-environment.htm

0 Response to "what adaptations allows the bird to stay in flight?"

Postar um comentário